By: Cindy Estis Green, CEO & Co-founder

Blog

Book Direct: The Numbers Tell the Story

Featured in the Summer 2016 issue of Hospitality Upgrade.

It's no secret that there have been a flurry of book direct campaigns launched in recent months. This includes IHG and Accor launching campaigns in Europe in 2015 followed by Hilton, Marriott, Hyatt, and IHG in the U.S. in 2016. This trend has raised many questions about how these campaigns will affect hotel performance from an owner and operator standpoint. Additionally, concerns have been raised by third-party OTAs and meta search vendors about how it may affect their own growth targets.

AGGRESSIVE RESPONSES FROM THE OTAS HAVE INCLUDED: letters to hotels claiming the book direct campaigns are not working, de-ranking and “dimming” of hotel listings and removal of participating hotels from preferred listing status. Both the CEO of Expedia and Booking.com have come out in public statements indicating they are not happy about the book direct campaigns and intimating that the large chain brands’ attempts will not succeed. The OTAs retaliatory actions convey a message that they sense a serious threat to their business.

Based on Kalibri Labs analysis, the data shows that direct brand.com bookings are significantly more profitable than OTA bookings, to the tune of a roughly 9 percent before factoring in ancillary spend which can take this to almost 18 percent. These findings are based on analysis of a database of daily stay and cost history from 25,000 hotels in the U.S. from 2011-present. On top of this, the acquisition costs for customers using direct channels decrease over time while those for OTA customers remain steady or may grow as commissions rise. Hotels essentially pay the same commissions every time a guest comes through an OTA; there is no reduction in cost when volume increases or guests come back. In contrast, as loyalty rosters grow, the overall marketing costs are reduced and the entire system becomes more efficient. The added advantage of direct engagement leads to improved relationships with guests.

The other factor regarding the OTA channel is that the presumed “billboard effect” benefit, touted by third parties as a mitigating factor in the high commission cost of their channels, has been shown to be a myth. The Online Travel Shopper’s Journey study published by the AH&LA Consumer Innovation Forum (released in Part I of Demystifying the Digital Marketplace) will explore this in detail, but the key finding from the 2015 study is that there is only a 7 percent probability that a consumer will visit an OTA and then return to brand.com to book.

Third-party business from OTAs, meta search, wholesalers and traditional travel agencies can be an important part of the mix, but a high level of dependence on any channel or segment that carries a high cost can prove risky. Striking the optimal balance between direct and indirect business sources will ultimately result in a hotel enjoying higher profit contribution, delivering better consumer experiences through higher levels of guest engagement, and yielding healthier economics for a hotel as a result of a diverse business base.

First, to frame the issue it may help to assess book direct from the hotelier’s point of view. While cost of acquisition is certainly an important factor, it is only one variable to consider. In addition to the direct cost savings, most hotels have found that there are other benefits of increasing the volume of business that is booked through direct channels. We have determined five benefits and will examine each of these benefits individually to evaluate its impact on a hotel.

The hotels in this sample, when combining the nearly 9% higher net ADR with the additional ancillary spend of Brand.com bookers, receive 17.9% higher net revenue from Brand.com bookings than those coming from the OTA channel.

-

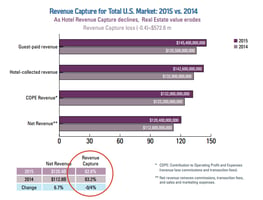

Lower cost of initial customer acquisition. When calculating the costs associated with a brand.com booking versus an OTA or meta search booking, it is helpful to compare both the direct costs as well as the net revenue and net ADR. Kalibri Labs refers to it as “COPE revenue” to reflect the revenue after removing direct transaction-related costs. The acronym COPE stands for Contribution to Operating Profit and Expenses and represents the percentage of revenue the hotel keeps for each channel after direct transaction fees are removed, such as commissions, channel costs and loyalty costs. Using upper upscale hotels as a sample in the U.S. market, the average brand.com booking has a COPE (or contribution) of 93.2 percent, which means it retains 93.2 percent of the guest paid revenue, while the average OTA booking yields only 82.7 percent. Of course, this includes a blend of retail, merchant and opaque OTA business so every hotel will vary. Even with the allocation of appropriate sales and marketing expenses and when all promotional rates including member pricing discounts are taken into account, the average net ADR is still almost 9 percent higher through brand.com.

-

Increased opportunity to use knowledge about a guest to personalize his or her experience. The knowledge about each guest can ensure that the products offered are consistent with what the guest is interested in receiving. Some guests would prefer to pay an upcharge for a deluxe accommodation and are happy to know when it is available. Some would like to take advantage of packages adding in parking or breakfast to the room charge. These kinds of offers are not easily managed currently on a third party site. In a full service or resort setting, hotels may have drinks, dining, spa or recreational offerings that can be sold in conjunction with the room. The benefit of getting that 10 a.m. massage appointment booked ahead of arrival compared to the experience of being told that all preferred time slots are already booked is a clear case of better serving guest needs. Using a select group of upper upscale hotels in the U.S. with a brand.com net ADR of $175 and the average length of stay of almost two nights, this guest type will yield an incremental $35 per stay in ancillary spend compared to those coming through an OTA channel with an average net ADR of $161 and less than two-thirds the ancillary spend. The hotels in this sample, when combining the nearly 9 percent higher net ADR with the additional ancillary spend of brand.com bookers, receive 17.9 percent higher net revenue from brand.com bookings than those coming from the OTA channel.

-

Opportunity to build on the relationship to get the guest to return to the same hotel or a sister hotel thereby reducing the recurring costs of customer acquisition. Many businesses calculate what is known as lifetime value analysis when evaluating the potential of their customer base. The cost of acquiring a guest the first time they come to a hotel is typically higher than the cost of getting that guest to return, making returning guests less costly over time. OTA business is predominantly not recurring, so hotels are constantly cycling through thousands of new customers. There are no economies of scale; that is, it is not possible to reduce the costs as sales volume increases and there is no difference in cost whether or not it’s a repeat visitor. Whether you are a large chain or a small independent, the hotel always pays a fixed premium as though each customer is a “first timer.” However, when a guest booking directly comes back multiple times, the higher sales and marketing expenses incurred on the first visit can be spread over future visits and total cost of acquisition over the guest’s “lifetime” use of a hotel are considerably lower. Hotels with a large recurring client base will generally be more efficient in customer acquisition spending, resulting in considerably higher net revenues.

-

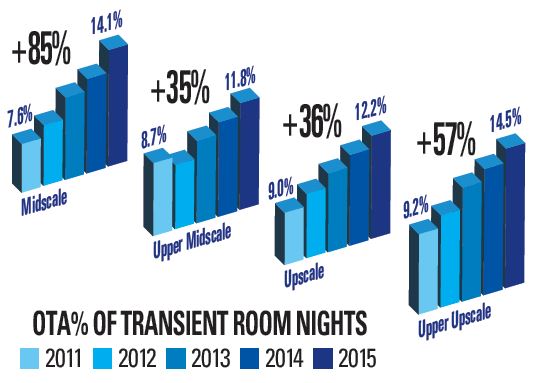

Diversifying the demand streams so the hotel is not beholden to one primary source for all of its business, a high risk during a down economy. There is a growing concern around rising cost of sales as U.S. hotels are now paying 15 percent to 25 percent of the guest paid revenue to acquire their customers. In the 2008-09 recession, when demand dropped precipitously to almost 9 percent below previous levels, hotels were willing to pay a premium to those who had control over that demand. This forced commission levels to rise from 20 percent to 25 percent, which was the norm at that time, to upwards of 30 percent to 40 percent. That was a time when OTA business made up 6 percent to 7 percent of total room nights for U.S. hotels. Now that it is closer to 15 percent, the next recession could be painful if hotels continue to grow dependency on a channel over which they have limited control and whose objectives may not be aligned with their own. A range of demand drivers for a hotel creates a healthy balance and mitigates the risk of losses during the inevitable downturns in the future.

-

Improved engagement with the guest provides a better experience and ensures that he/she gets what was expected upon booking. Hotels have always scored considerably better than other sectors of travel in terms of consumer satisfaction. Hotels play important roles in their communities and part of that is driven by the experience hotels provide to their guests. The ability to build relationships with guests is better served when a hotel can communicate pre-stay, during the stay and post-stay. With or without a loyalty program, a hotel's ultimate success depends on its ability to deliver a differentiated guest experience and to engage the guest at every point of contact to that end. Few OTA customers are committed to hotel loyalty programs as they usually do not receive points for those visits. The focus for OTAs to build their own relationship with these customers also puts some obstacles between the guest and the hotel. Adding in the scams and other forms of deception, even the FTC is recommending that consumers are more likely to get what they expect by booking directly.